Arlington, TX — The U.S. Postal Service will pay tribute to the sacrifices of 12 civil rights pioneers Saturday with the official first day of issue release of a six-stamp set at a ceremony during the annual meeting of the NAACP in New York City. A first day of sales stamp ceremony will be also be held Saturday morning at 11 a.m., February 21, as part of the AmeriStamp Expo/ TEXPEX, February 20-22, 2009 at the Arlington Convention Center, 1200 Ballpark Way, Arlington, TX.

Elzie Delano Odom, the first African-American mayor of Arlington, Texas (1997-2003) and the fifth African-American U.S. Postal Inspector (1967); President Rita Sibert and Vice-President James Rose, of the NAACP, Arlington, Texas Chapter; Wade Saadi, President, American Philatelic Society; Wayne Saxton, Postmaster, Arlington, TX; and other Postal Service and community officials will be participating in the Arlington, TX first day stamp event.

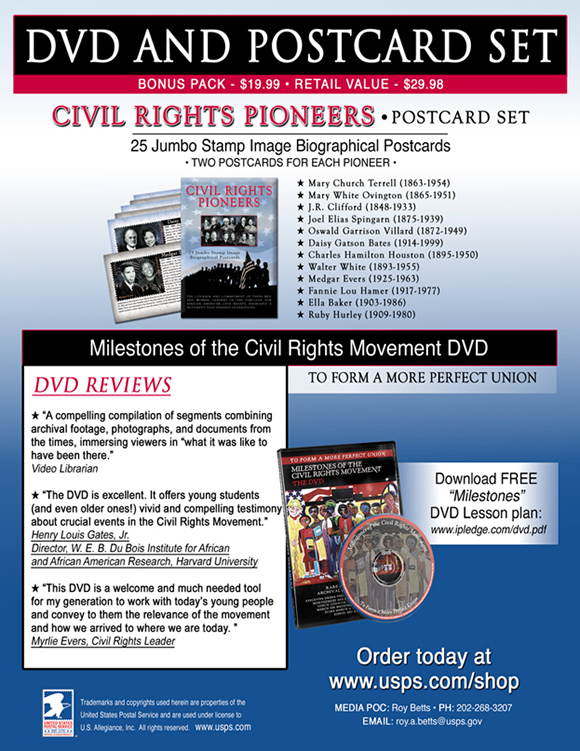

The six, 42-cent First-Class commemorative stamps honor the achievements of Ella Baker, Daisy Gatson Bates, J.R. Clifford, Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Charles Hamilton Houston, Ruby Hurley, Mary White Ovington, Joel Elias Spingarn, Mary Church Terrell, Oswald Garrison Villard and Walter White.

In addition to the stamps, the Postal Service is offering several philatelic products, including a Civil Rights Pioneer Cultural Diary Page and a DVD and postcard set. Go online to the Postal Store, http://shop.usps.com for displays and information on these and other products.

Art director Ethel Kessler and stamp designer Greg Berger, both of Bethesda, MD, chose to approach this project through photographic montage. Pairing two pioneers in each stamp was a way of intensifying the montage effect. The selvage image, or area outside of the stamps, is an illustration by Greg Berger showing participants in a march.

Top row of stamps:

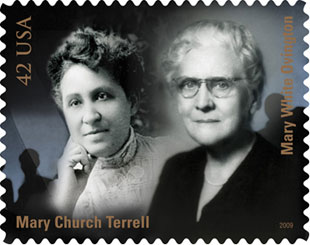

Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954)

Throughout her long life as a writer, activist, and lecturer, she was a powerful advocate for racial justice and women’s rights in America and abroad. The portrait of Mary Church Terrell, from the collection of the Library of Congress, was made between 1880 and 1900.

Mary White Ovington (1865-1951)

This journalist and social worker believed passionately in racial equality and was a founder of the NAACP. The photograph of Mary White Ovington was taken between 1930 and 1940. It is part of the NAACP archival collection at the Library of Congress.

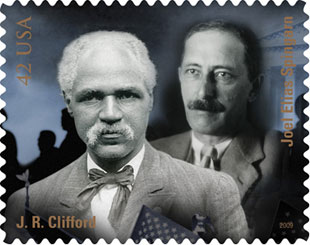

J.R. Clifford (1848-1933)

Clifford was the first black attorney licensed in West Virginia. In two landmark cases before his state’s Supreme Court, he attacked racial discrimination in education. The image of J.R. Clifford is a detail from an undated photograph from the University of Massachusetts Library Special Collections.

Joel Elias Spingarn (1875-1939)

Because coverage of blacks in the media tended to be negative, he endowed the prestigious Spingarn Medal, awarded annually since 1915, to highlight black achievement. The portrait of Joel Elias Spingarn is dated in the 1920s and comes from the records of NAACP at the Library of Congress.

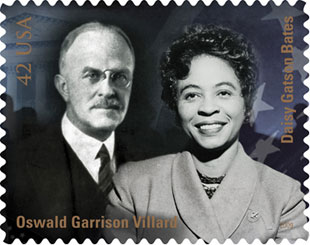

Oswald Garrison Villard (1872-1949)

Villard was one of the founders of the NAACP and wrote “The Call” leading to its formation. His undated portrait comes from the records of the NAACP at the Library of Congress.

Daisy Gatson Bates (1914-1999)

Bates mentored nine black students who enrolled at all-white Central High School in Little Rock, AR, in 1957. The students used her home as an organizational hub. The 1957 photograph of Bates is from the New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper photographic collection at the Library of Congress.

Bottom row of stamps:

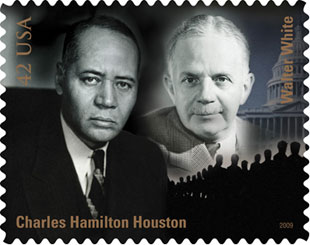

Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950)

This lawyer and educator was a main architect of the civil rights movement. He believed in using laws to better the lives of underprivileged citizens. Houston’s portrait is a Nov. 22, 1939, photograph from the Washington Press obtained from the Library of Congress.

Walter White (1893-1955)

Blue eyes and a fair complexion enabled this leader of the NAACP to make daring undercover investigations. The portrait of Walter White, dated around 1950, is from the records of the NAACP at the Library of Congress.

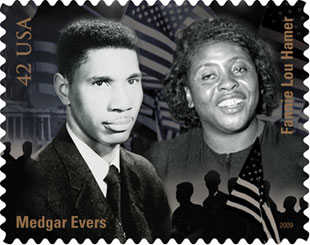

Medgar Evers (1925-1963)

Evers served with distinction as an official of the NAACP in Mississippi until his assassination in 1963. The photograph of Evers is from the Library of Congress.

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977)

Hamer was a Mississippi sharecropper who fought for black voting rights and spoke for many when she said, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Her portrait is dated Aug. 24, 1964.

Ella Baker (1903-1986)

Baker’s lifetime of activism made her a skillful organizer. She encouraged women and young people to assume positions of leadership in the civil rights movement. The portrait of Ella Baker is dated between 1943 and 1946 and is from NAACP records at the Library of Congress.

Ruby Hurley (1909-1980)

As a courageous and capable official with the NAACP, she did difficult, dangerous work in the South. Hurley’s image is from a 1963 newspaper photo.

Civil Rights Pioneers

Background Information

Ella Baker b. Dec. 13, 1903, Norfolk, VA; d. Dec. 13, 1986, New York, NY

For decades, the legal strategies of the NAACP made it the most powerful civil rights group in America. In the 1950s and ’60s, the focus of the movement shifted from North to South, from courtrooms to direct action in the marketplace and the streets. A guiding spirit behind these changes was Ella Baker, whose lifetime of activism made her a vital link between two broad phases of the civil rights movement.

Ella Baker was born on Dec. 13, 1903, in Norfolk, VA, and was the granddaughter of former slaves. After graduating in 1927 as class valedictorian from Shaw University, a historically black college in North Carolina, Baker made her way north to New York City and soon plunged into progressive politics.

In New York, Baker joined many diverse groups, serving in both paid and volunteer positions. She took a job with a program designed to help workers achieve literacy and other skills. She also worked with various women’s groups and was the co-author of an investigative article on African-American domestic workers.

Baker traveled through the South in the 1940s organizing NAACP chapters. In the late 1950s, she moved to Atlanta to work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Though she respected its president, Martin Luther King Jr., Baker felt the group’s emphasis on leadership from the top down was a mistake.

In 1960, after the eruption of the lunch counter sit-in movement, Baker organized a conference for student leaders. From this conference, held on the campus of Shaw University, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) emerged. Baker helped the students realize that they were an important social force in their own right, thus influencing the later youth movements of the 1960s.

“Most of the youngsters had been trained to believe in or to follow adults if they could,” she said. “I felt they ought to have a chance to learn to think things through and to make decisions.”

Before the Democratic National Convention in 1964, in an effort to persuade the party to establish rules ensuring the inclusion of black delegates, Baker helped to found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. She subsequently moved back to New York City, where she remained active in various progressive causes.

Baker encouraged women and young people to join the civil rights movement and to assume positions of leadership. This exceptionally skillful organizer and major figure in the struggle for equality died at her home in New York on Dec. 13, 1986, her 83rd birthday.

Daisy Gatson Bates b. Nov. 11, 1914, Huttig, AR; d. Nov. 4, 1999, Little Rock, AR

A highly visible challenge to school segregation was issued in Arkansas in 1957, when nine black students enrolled at Little Rock’s Central High School in the glare of worldwide publicity. Their advisor and central supporter was Daisy Gatson Bates, a newspaperwoman and president of the NAACP’s Arkansas chapter.

Gatson was born on Nov. 11, 1914, in Huttig, a small town in southern Arkansas. As a young woman, she moved with her husband, L.C. Bates, to Little Rock, where they established the State Press, a weekly newspaper. She reported on various issues, including discrimination against black soldiers stationed in Arkansas during World War II and later, attempts made by black students to register at all-white schools.

In addition to her newspaper work, Bates expressed her activism as Arkansas state president of the NAACP, also serving as an advisor to the organization’s local Youth Council. By 1957, when nine young African-Americans enrolled at the all-white Central High School, Bates was an experienced and capable leader. That August, shortly before integration was scheduled to begin, a rock came crashing through her window with a message reading: “Stone this time. Dynamite next.”

Undaunted, Bates offered her home as an organizational hub for the students. They met there in the morning and again at the end of the day. One of the students, Thelma Mothershed, later remembered: “That’s when we gained our support from each other — who had done what and what had happened to who and this sort of thing.”

The students needed support. They faced angry, jeering mobs barely controlled by the federal troops sent by President Eisenhower. Some citizens of Little Rock felt that their city had been invaded; others realized that the troops were there to preserve order. In her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock (1962), Bates recalled being asked if she was happy that troops had arrived to protect the nine students and larger community against racist violence. Her response: “Any time it takes 11,500 soldiers to assure nine Negro children their constitutional right in a democratic society, I can’t be happy.”

In 1958, Bates joined Martin Luther King Jr., and others to watch Ernie Green, the senior among the nine students, receive his diploma. That same year, she and the “Little Rock Nine” were awarded the Spingarn Medal. In 1963, Daisy Gatson Bates spoke at the March on Washington. She died at age 84 on Nov. 4, 1999, in Little Rock.

J.R. Clifford b. Sept. 13, 1848, in present-day WV; d. Oct. 6, 1933, Martinsburg, WV

Many important battles in the African-American struggle for civil rights have been fought in the courts. Lawyers like John Robert Clifford, the first black attorney licensed in West Virginia, played leading roles in these dramas. Clifford argued two landmark cases, in which he attacked racial discrimination in schools, before his state’s Supreme Court.

The most probable of various dates given for the birth of J.R. Clifford is Sept. 13, 1848. He was born in Virginia, in the region now known as the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia. His parents sent him to be educated in Chicago, but he left school during the Civil War and joined the Union Army despite being too young to enlist — a fact that accounts for some of the confusion surrounding his birth date.

In the 1870s, back in West Virginia, Clifford began coursework at Storer College, then a new school for blacks. He graduated in 1877 and became a teacher, then principal, in a school in Martinsburg. In 1882, he established the Pioneer Press, a successful black newspaper. He passed the West Virginia bar exam in 1887 and began to practice law.

In Martin v. Board of Education of Morgan County, Clifford represented Thomas Martin, an African American who wanted his children to attend the local white school since there was no school for blacks. He did not prevail: The West Virginia Supreme Court ruled in 1896 that the state law mandating separate schools for blacks and whites was not unconstitutional. However, the court cited the “neglect” of Morgan County to fulfill its responsibility for educating its black citizens, and a “colored school” was subsequently established.

In 1898, Clifford won an important victory in Williams v. Board of Education of Fairfax District. That case stemmed from the school board’s decision to shorten the school year for black children as an economizing measure. When Clifford was approached by teacher Carrie Williams for help, he advised her to keep teaching for the full term and then filed a lawsuit for her back pay. He won the case before a jury, and then won again on appeal before the state Supreme Court, bolstering arguments that blacks were entitled to equal rights in education.

With W.E.B. DuBois and other black leaders, Clifford was a founder of the Niagara Movement, a group that called for full civic equality for black Americans and influenced the NAACP’s formation.

Clifford died on Oct. 6, 1933, in a hospital in Martinsburg, after a fall at his home.

Medgar Evers b. July 2, 1925, Decatur, MS; d. June 12, 1963, Jackson, MS

The African-American struggle for civil rights claimed many martyrs. One of these heroes was Medgar Evers, an official of the NAACP in Mississippi. Addressing a crowd in June of 1963, Evers said: “I love my children and I love my wife with all my heart. And I would die, and die gladly, if that would make a better life for them.” Days later, he was assassinated.

Evers was born on July 2, 1925, in Decatur, MS. Friends and family members later remembered him as a serious child. During World War II, Evers served in Normandy with the U.S. Army; back in Mississippi after the war’s end, he was determined to win the freedom he had defended. He graduated from Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University) and applied for admission to the University of Mississippi School of Law — all white at that time — but was rejected.

He subsequently accepted a position with the NAACP. As the organization’s first field secretary in Mississippi, Evers risked his personal safety to investigate acts of racial violence against African-Americans. At this time in the 1950s, nearly half of Mississippi’s population was black — many counties had black majorities — but only a few black Mississippians were registered to vote. As part of his duties, Evers led voter registration drives and organized consumer boycotts; working undercover, he investigated the murder of Emmett Till, a black youth from Chicago who was killed while visiting relatives in Mississippi. Evers also played an active role in supporting James Meredith’s attempt to enroll at the University of Mississippi, which was forced to desegregate in 1962.

As time went on and his achievements were recognized, Evers became more visible to friends and enemies alike. In the weeks leading up to his death, his home in Jackson was firebombed and threats were made on his life. His wife, Myrlie, later remembered receiving threats by mail and by phone. “It was a life,” she said, “of never knowing when that bullet was going to hit.”

Around midnight on the evening of June 11, 1963, Evers returned home after working late. When he parked his car in the driveway and stepped outside, gunfire rang out. He died at the age of 37 in the early morning hours of June 12. His assassin was ultimately convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Evers was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. He was posthumously awarded the Spingarn Medal. The Medgar Evers papers and artifacts are housed at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, in Jackson.

Fannie Lou Hamer b. Oct. 6, 1917, Montgomery County, MS; d. March 14, 1977, Mound Bayou, MS

Lack of access to the political process was long a factor in keeping black Americans oppressed by poverty and segregation. This was the key insight of Fannie Lou Hamer, a leading activist of the civil rights movement. Despite fierce opposition, she encouraged African-Americans to take part in the democratic process.

The youngest of 20 children in a family of sharecroppers, Hamer was born on Oct. 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, MS. She was still a child when she first picked cotton in the fields. Though she lacked formal education, she demonstrated obvious intelligence throughout her life and became a brilliant communicator. She spoke for many when she said, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” — words later carved on her tombstone.

Hamer was in her 40s when she entered the civil rights movement. For most of her life, she had been unaware that she had the right to vote. When she tried to register in 1962, she lost her job and was beaten and shot at. Commenting later on the courage she showed in attempting to exercise her right, she remarked: “I guess if I’d had any sense I’d have been a little scared, but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do to me was kill me, and it seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time ever since I could remember.”

In 1964, Hamer won national attention representing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), a response to the exclusion of blacks by the all-white state party. With an integrated slate of delegates, Hamer attended the party’s national convention in Atlantic City, NJ, arguing that MFDP was the legitimate delegation from the state of Mississippi since it was the only one open to all citizens of voting age. On national television, Hamer said, “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America? The land of the free and the home of the brave?” The “freedom delegates” made an unforgettable impression and laid the path for future success. Hamer was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968.

When a group of activists traveled to Africa in the fall of 1964, Hamer accompanied them. She was moved when President Sékou Touré of Guinea offered words of encouragement.

Hamer remained active in various campaigns to expand educational and economic opportunities for blacks. She was awarded honorary degrees by many colleges and universities. This great American activist died March 14, 1977, in Mound Bayou, MS.

Charles Hamilton Houston b. Sept. 3, 1895, Washington, DC; d. April 22, 1950, Washington, DC

For many decades in America, the faulty legal doctrine that blacks and whites should be treated as “separate but equal” made racial segregation common in schools, restaurants, and other public facilities. This flawed reasoning and the inequality it purported to justify were attacked by a generation of lawyers, many of them trained by one man — Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP’s first black special counsel, and before that a brilliant educator who headed the Howard University School of Law.

Houston was born Sept. 3, 1895, in Washington, DC, where his father had a law firm. His decision to follow in the parental footsteps was prompted by the discrimination he saw firsthand when serving in the U.S. Army during World War I. He was a superior student, excelling both at Amherst College, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa honor society while earning an undergraduate degree, and Harvard University, where he studied law and became the first black editor of the Harvard Law Review.

While working for his father’s firm and teaching in the Howard University School of Law, Houston began to put his ideas into practice. He believed in using the law to better the lives of underprivileged citizens and in a progressive approach to jurisprudence that relied on sociological evidence as well as legal precedent in reasoning and argument. “A lawyer’s either a social engineer,” Houston remarked, “or he’s a parasite on society.”

As chief counsel of the NAACP beginning in 1935, Houston traveled widely, speaking to audiences and battling discrimination in various courtrooms. His strategy for ending segregation was to concentrate first on education, working from the college level down, on the theory that integrating older students would be less threatening to the public. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its historic ruling against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas — a decision that paved the way for further assaults on systematic discrimination.

Unfortunately, Houston didn’t live to see it. He died at age 54, on April 22, 1950. That same year, he was posthumously awarded the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in honor of his championship of equality. He is remembered for being one of the main architects of the civil rights movement and for training many of its leading lawyers. One of his students was Thurgood Marshall, who succeeded him as chief counsel of the NAACP and later became a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. In 1958, Howard University named the main building of its law school in Houston’s honor.

Ruby Hurley b. Nov. 7, 1909, Washington, DC; d. Aug. 9, 1980, Atlanta, GA

Ruby Hurley may not have been as highly visible as other leaders in the civil rights movement, but this courageous and capable woman was a powerful force both in and out of the glare of the spotlight. As an NAACP official, she did difficult and dangerous work in several Southern states.

Hurley was born on Nov. 7, 1909, in Washington, DC, where she studied law at the Robert H. Terrell Law School, an institution that allowed its largely black student population to take classes at night. Her introduction to civil rights activism came when she helped organize Marian Anderson’s celebrated concert at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, 1939, after the classical contralto was barred from Constitution Hall due to a “white performers only” policy. That same year, Hurley began working with the NAACP in Washington. She developed a local youth council and, during the 1940s, traveled around the country organizing and supervising college chapters and youth councils for the association, dramatically increasing their number.

In 1951, Hurley was transferred to Birmingham, AL, where she opened the first full-time NAACP office in the Deep South, attracting fierce opposition. She was charged with organizing new NAACP branches throughout the region. Hurley investigated violent racial crimes including the 1955 murders of George W. Lee and Lamar Smith, who had been active in a drive to register black voters in Mississippi. That same year, with Medgar Evers and others, Hurley investigated the murder of Emmett Till, a black youth from Chicago who was killed while visiting an uncle in Mississippi. She courageously went with colleagues to search for evidence on the farm of one of Till’s killers. Throughout this time, Hurley was subject to death threats and violence.

When the state of Alabama outlawed the NAACP in 1956, Hurley was spirited away by night to Atlanta, where she set up another NAACP office. There, she was noted for defending the strategies of her generation of civil rights workers to the younger generation of activists.

Hurley usually relied on legal grounds to make her point, but could also speak with forceful informality, as she did while discussing lunch-counter sit-ins in 1960. After citing the U.S. Constitution, Hurley exclaimed, “What we’re saying, Mr. White Folks, is this: You wrote it, and all we want you to do is live by it!”

A little more than two years after her retirement from the NAACP, Hurley died at home in Atlanta on Aug. 9, 1980, at the age of 70.

Mary White Ovington b. April 11, 1865, Brooklyn, NY; d. July 15, 1951, Greater Boston, MA

“So closely is the life of Mary White Ovington woven into the work of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People that to talk of one is to talk of the other.” The preceding sentence appears in a New York Times review of Ovington’s historical and autobiographical book The Walls Came Tumbling Down, published in 1947.

Mary White Ovington was born into a progressive family in Brooklyn, NY, on April 11, 1865. She entered the Harvard Annex (later Radcliffe College) as a young woman, but left school after an economic downturn threatened her father’s business. She grew interested in socialism, became a pacifist and an advocate for the poor, and was especially devoted to the cause of racial equality.

Back in Brooklyn, she became the registrar of the newly established Pratt Institute and then resigned to take a job working with impoverished immigrants in a settlement community. Settlements, or “housing projects” where privileged citizens worked with the disadvantaged in urban settings, had recently spread to America from England.

Hoping to create an interracial settlement house, Ovington began a serious study of the lives of black New Yorkers. Her studies resulted in the publication of Half a Man: The Status of the Negro in New York (1911), in which she argued that racism kept black people from realizing their potential. “If we deny full expression to a race,” she wrote, “if we restrict its education, stifle its intellectual and aesthetic impulses, we make it impossible fairly to gauge its ability.”

For much of her life, Ovington worked part-time as a journalist. In 1906, on assignment for the New York Evening Post, she attended a meeting of the Niagara Movement, a civil rights organization, where she cemented a friendship with black leader W. E. B. Du Bois. Her other works include articles published in various periodicals and the book Portraits in Color (1927), describing notable black Americans.

After reading a newspaper piece on racial violence in Illinois in 1908, Ovington used her skill at bringing diverse personalities together to form a committee to discuss racial issues. That group issued a call signed by more than 50 prominent citizens, both black and white, for a national conference on the problems of black Americans. Out of this series of conferences and meetings the NAACP was formed, with Ovington serving in various executive positions for nearly 40 years. She retired in 1947 and died at the age on 86 on July 15, 1951, in a suburb of Boston, MA, where she had gone to be with her sister.

Joel Elias Spingarn b. New York City, May 17, 1875; d. New York City, July 26, 1939

The prestigious Spingarn Medal, for “the man or woman of African descent and American citizenship who has made the highest achievement during the preceding year in any honorable field,” was first presented in 1915. Since then, it has been awarded annually to such noted figures as baseball great Hank Aaron, entertainer Bill Cosby, jazz legend Duke Ellington, civil rights leader Rosa Parks, painter Jacob Lawrence, opera singer Leontyne Price, and media personality Oprah Winfrey. In 2007, the prize was presented to Congressman John Conyers (D-MI). Less widely known is the person who established the award, for whom it is named.

Joel Elias Spingarn, a leading figure during the NAACP’s first three decades, was born on May 17, 1875, to Jewish immigrants in New York City. His father was a wealthy merchant; the younger Spingarn became an educator, literary critic, horticulturist and activist in liberal causes. He was a professor in the department of comparative literature at Columbia University for several years, until his criticism of the school’s administration resulted in his dismissal. After leaving his post at Columbia, he concentrated on literary pursuits, horticulture and social activism.

His commitment to racial justice prompted Spingarn to devote time and resources toward building up the NAACP during its early years. Spingarn offered skillful leadership, serving in various executive positions. His brother Arthur provided the association with legal counsel.

One of Spingarn’s key insights was that coverage of blacks in the media was woefully insufficient and tended to focus on negative stereotypes and criminality. To combat this unfortunate trend, he endowed an award that would highlight black achievement. He formed a committee of prominent citizens to administer the prize, giving them free choice as to category; the first medal bearing his name was presented in 1915, to biologist Ernest E. Just.

In the belief that nothing would change for blacks until both women and blacks had the vote, Spingarn advocated voting rights for women. He encouraged black writers of the Harlem Renaissance, the period during the 1920s when African-American arts flourished in New York and elsewhere.

Spingarn produced books of poetry and literary criticism and was a co-founder of the publishing house Harcourt, Brace and Company. He pursued his horticultural interests at his country estate in Amenia, New York, where he also hosted African-Americans in meetings at pivotal moments in the NAACP’s history. Spingarn died in New York City on July 26, 1939.

Mary Church Terrell, b. Memphis, TN: Sept. 23, 1863; d. Annapolis, MD, July 24, 1954

In her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, published in 1940, educator and activist Mary Church Terrell identified herself as a member of two oppressed groups. “A white woman,” she noted, “has only one handicap to overcome — that of sex. I have two — both sex and race.”

Mary Church was born on Sept. 23, 1863, in Memphis, TN. “It nearly killed me to think that my dear grandmother, whom I loved so devotedly, had once been a slave,” Terrell wrote later, adding her grandmother’s reassuring words: “Never mind, honey. Gramma ain’t a slave no more.” Mary’s hard-working parents, who had also been slaves, could afford to send their daughter to school in the North. At Oberlin College, she pursued a classical program of studies and earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

As a young woman, she studied abroad before marrying Robert Terrell, who later became a judge in Washington, DC. In 1895, she was appointed to the Washington school board, becoming one of the first black women in America appointed to such a post. She spent decades working to win the vote for women and was a charter member of the National Association of Colored Women, becoming the group’s first president in 1896.

In 1892, after a man she knew was lynched in Memphis, Terrell and her friend Frederick Douglass demanded a meeting with President Benjamin Harrison and urged him to issue a statement condemning lynching. Harrison declined to do so.

Terrell lectured widely here and abroad on the effects of racism and the status of women, impressing European listeners by giving speeches in multiple languages. She wrote a short tribute to Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in observance of the centenary of Stowe’s birth, and published articles in various periodicals and newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the Boston Herald.

Terrell was one of the prominent citizens who signed “The Call” for the NAACP. She advocated protest and resistance against injustice; her endorsement of boycotts, sit-ins and picket lines earned her a reputation for being “militant.” She remained active into her late 80s, when she took part in campaigns to desegregate schools and restaurants in Washington.

Throughout her life, as a writer, activist, and lecturer, Terrell was a powerful advocate for racial justice and women’s rights. She died at the age of 90 on July 24, 1954, in Annapolis, MD, near her home in Highland Beach. A collection of her papers is in the Library of Congress.

O.G. Villard b. March 13, 1872 Germany; d. Oct. 1, 1949 New York City

A spirit of liberal reform distinguished the family of journalist Oswald Garrison Villard, one of the NAACP’s founders. His maternal grandfather was the noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Though he championed many causes, Villard’s work on behalf of racial equality remains his greatest legacy.

Villard was born on March 13, 1872, in Wiesbaden, Germany. His father was a railroad and publishing magnate. After earning undergraduate and graduate degrees at Harvard, Villard took over as editor of his father’s newspaper, the New York Evening Post. Under his leadership, the paper endorsed political candidates who were thought to be more liberal on racial issues.

When reports of racial violence in Illinois in 1908 spurred Mary White Ovington to bring concerned citizens together, Villard volunteered to draft a call for a conference devoted to the complete emancipation of black Americans. In light of Abraham Lincoln’s reputation as the “Great Emancipator” who freed the country’s slaves, the call was strategically issued on the centennial of Lincoln’s birth, Feb. 12, 1909. “The Call,” as Villard’s document was known, is a small masterpiece.

“Besides a day of rejoicing, Lincoln’s birthday in 1909 should be one of taking stock of the nation’s progress since 1865,” Villard wrote. He decried racial discrimination, particularly widespread at that time in the South, where black citizens were denied voting rights and had to use separate sections of buses, trains and various public accommodations. “Silence under these conditions means tacit approval,” Villard continued. His closing words were “Hence we call upon all the believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewal of the struggle for civil and political liberty.”

The Call was signed by a large group of prominent citizens, both black and white, and eventually resulted in the formation of the NAACP. With the association’s incorporation in 1911, Villard was named chairman of its board of directors. He gave the new organization space in the offices of the Evening Post.

Villard was a pacifist who opposed U.S. entry into war. He advocated equal rights for women, supported calls for fair labor practices, and was an early member of the American Civil Liberties Union. As editor of The Nation, he helped organize the campaign to save Sacco and Vanzetti, anarchists who were executed in 1927 despite international protest. Villard died in New York City on Oct. 1, 1949, at the age of 77.

Walter White b. July 1, 1893, Atlanta, GA; d. March 21, 1955, New York City

As leader of the NAACP for more than two decades, Walter White was a powerful force in the civil rights movement. Given his straight blond hair, blue eyes, and fair complexion, White’s choice to identify as black presented a challenge to people’s preconceptions. His appearance enabled him to make daring undercover investigations of racially motivated violence against African Americans.

White was born on July 1, 1893, in Atlanta, where his father worked for the Post Office. In his autobiography, A Man Called White (1948), he described being deeply affected at the age of 13 when an angry white mob threatened him and his household.

After helping to establish the Atlanta branch of the NAACP — then a new organization — White was brought to the group’s office in New York and given the task of investigating lynchings. His book-length study on the topic, Rope and Faggot, was published in 1929. White’s other books include two novels on racial themes, The Fire in the Flint (1924) and Flight (1926). In A Rising Wind (1945), he reported on the discrimination faced by black American troops during World War II.

Under White’s skillful leadership, the NAACP tackled many problems of African-American life and became a major force in American society at a time when integration was widely regarded as a radical notion. White lobbied for civil rights legislation, protested against discrimination in the U.S. military, and argued against school segregation. He advised Presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman on civil rights issues. He was also an effective fundraiser.

In 1937, White was awarded the Spingarn Medal in honor of his fight for federal anti-lynching legislation and the courage he had shown while investigating dozens of lynchings.

Calling for an end to discrimination against people of color and for their accurate representations in the media, White served as a consultant to the U.S. delegation to the United Nations at its founding in 1945.

White was sometimes criticized for running the NAACP as a “one-man show,” but he recruited other individuals to the organization who complemented his strengths, including Charles Hamilton Houston, who led the legal campaign that culminated in 1954 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling, in Brown v. Board of Education, that school segregation was illegal.

White died of a heart attack in his New York City home at the age of 61 on March 21, 1955.

# # #

Please Note:

For broadcast quality video and audio, photo stills and other media resources, visit the USPS Newsroom at www.usps.com/communications/newsroom/welcome.htm.

An independent federal agency, the U.S. Postal Service is the only delivery service that reaches every address in the nation, 146 million homes and businesses, six days a week. It has 37,000 retail locations and relies on the sale of postage, products and services, not tax dollars, to pay for operating expenses. The Postal Service has annual revenue of $75 billion and delivers nearly half the world’s mail. To learn about the history of the Postal Service visit the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum: www.postalmuseum.si.edu. An independent federal agency, the U.S. Postal Service is the only delivery service that visits every address in the nation — 146 million homes and businesses. It has 37,000 retail locations and relies on the sale of postage, products and services to pay for operating expenses, not tax dollars. The Postal Service has annual revenues of $75 billion and delivers nearly half the world’s mail.