|

Debt

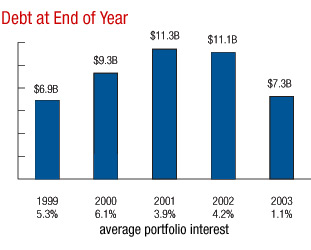

The amount we borrow is largely determined by the difference between our cash flow from operations and our capital cash outlays. Our capital cash outlays are the funds we invest back into the business for our capital investments in new facilities, new automation equipment and new services. From 1997 through 2002, our outlays for capital investment exceeded cash from operations by $5.6 billion, so we covered the difference with borrowed funds. From the end of 1997, which was the lowest end-of-year debt level in the last 10 years, to the end of 2002, our debt outstanding to the Department of the Treasury's Federal Financing Bank increased from $5.9 billion to $11.1 billion.

Our debt management strategy has been

based on the assumption that we would

always have a core amount of debt outstanding.

Therefore, we have maintained a mixture

of fixed- and floating-rate debt, striking a

balance between short- and long-term debt.

Thus, as interest rates declined to historically

low levels during 2002, we shifted the balance

of our debt portfolio toward more fixed-rate,

long-term debt in order to protect ourselves

against future increases in interest rates.

Under this strategy, we began 2003 with $7.3

billion in long-term debt that carried a

weighted-average interest rate of 5.1%.

With the enactment of the Postal Civil

Service Retirement System Funding Reform

Act of 2003 (Act), we had to completely

change our debt management strategy. The

Act requires us to apply all cash savings we

realize under its provisions in 2003 and 2004

to debt reduction. In 2005, we must use any

savings to maintain steady postal rates and to

reduce debt. Congress has yet to state how we

are to use any savings realized after 2005.

We could have achieved the required debt

reduction for 2003 by paying off short-term

debt. However, the requirement for 2004, estimated

at $2.7 billion, would have been a

challenge because only $750 million of our

debt was scheduled to mature. In other words,

we would have had to prepay some long-term

debt before maturity at an unknown price. We

|

|

decided instead to retire more long-term debt

this year so we will have the flexibility to

reduce debt next year without a penalty.

The repurchase price of our debt depends

on the interest rates for Treasury securities

with maturity dates and terms similar to our

debt. If the interest rate for Treasury securities

falls below the level at which our debt was

issued, we have to pay a premium to pay off

our debt. If interest rates are roughly equivalent

to the interest rates at the time we

incurred the debt, we do not have to pay a

premium.

Before the passage of the Act, we had

already undertaken steps to refinance and

reduce our outstanding debt. In January we

paid off $777 million in long-term debt without

a net premium. In July, following enactment of

the Act, we retired an additional $547 million,

for a total of $1.3 billion. Because we did not

have to pay a premium to retire this debt, we

realized net savings from these transactions

immediately, through lower interest expense.

The weighted average interest rate for the

retired debt was 4.5%.

In August, we used more favorable market conditions to retire our remaining $6 billion of long-term debt by paying a premium of $360 million, a charge to this year's net income. The retired debt carried an average interest rate of |

|

|