Steamboats

At the turn of the 19th century, when the nation’s waterways were its main transportation arteries, travel often depended on river currents, wind and muscle. Traveling upstream on some rivers was so difficult that boat owners sometimes sold their vessels upon reaching their destination and returned home overland.

Robert Fulton launched America’s first commercial steamboat line, connecting New York City and Albany via the Hudson River, in September 1807. Although Fulton's steamboats traveled at only six miles per hour, their dependability revolutionized travel. As long as their fires were fed, the boats’ boilers created steam, turning the paddlewheels.

On October 2, 1807, the New-York Evening Post asked

would it not be well if she [the boat] could contract with the Post Master General to carry the mail from this [city] to Albany?

Fulton’s steamboat carried mail as early as November 1808. Initially letters were carried either unofficially by crew and passengers – bypassing local Post Offices – or under the existing provisions for ship letters, whereby postmasters at ports of call gave ship captains two cents for each letter and then charged letter recipients six cents postage. In 1810 Postmaster General Gideon Granger offered Fulton a contract to carry mail, but Fulton apparently declined.

The New Orleans, the first commercial steamboat to ply the lower Mississippi River, began carrying mail from New Orleans to Natchez, Mississippi, in 1812 – also without a mail contract. In December 1812 John Hankinson, postmaster of Natchez, alerted Granger to the drop in his office’s revenue as more and more letters bypassed the Post Office. In 1813 Congress authorized the Postmaster General to contract for the carriage of mail by steamboat, provided it was no more expensive than if transported by land (2 Stat. 805). Granger informed Hankinson that he could enter into a mail transportation contract with the captain of the New Orleans, but apparently no contract was made.

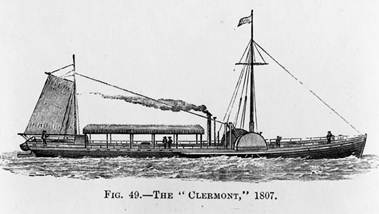

Robert Fulton’s Clermont, 1807

Although popularly associated with New Orleans and the Mississippi River, steamboats were first used commercially on the Hudson River in New York, connecting New York City with the state’s capital, Albany.

(illustration from The Steam Engine and Its Inventors: A Historical Sketch, by Robert L. Galloway, 1881; courtesy Library of Congress).

On February 27, 1815, Congress authorized the Postmaster General to contract for the carriage of mail by steamboat “on such terms and conditions as shall be considered expedient” and required the operators of steamboats and other craft to promptly deliver any letters they carried to postmasters at ports of call, under penalty of a fine (3 Stat. 220). The next month, the steamboat captains on the Hudson River line entered into a contract with the Postmaster General. Steamboats on the Mississippi River, meanwhile, continued to transport letters either outside of the U.S. Mail or as ship letters.

To help limit revenue losses, in 1823 Congress declared waterways upon which steamboats regularly traveled to be post roads (3 Stat. 767), making it illegal for private express companies to carry mail on them.

By the late 1820s the Post Office Department had contracted for mail to be carried by steamboats along the East Coast, between New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and from Washington, D.C., to Richmond. Mail contractors continued to use stagecoaches on parts of the routes and used stagecoaches exclusively when waterways were clogged with ice in winter. By 1827 steamboats were also carrying mail under contract between Mobile, Alabama, and New Orleans.

By the early 1830s contracted service began on the Ohio River from present-day Huntington, West Virginia, via Cincinnati, to Louisville, Kentucky – but no further west. Postmaster General Amos Kendall stated in his 1835 report to the President that an “immense correspondence” was carried in steamboats, postage-free, west of Louisville. He noted that where there was no contracted service it was “difficult, if not impractical, to enforce the Post Office laws, and bring the letters so transmitted into the post offices.”[1]

Contracted steamboat service west of Louisville, to New Orleans, began in November 1837. Nevertheless, many merchants continued to send their correspondence outside the U.S. Mail, postage-free.

In the mid-1800s the Post Office Department greatly expanded its use of steamboats to carry mail. Between 1845 and 1855 the distance that mail was transported by steamboat nearly doubled, from 7,625 to 14,619 miles.

In November 1848 Postmaster General Cave Johnson dispatched a special agent to establish Post Offices in the newly-acquired territory of California. By Christmas, steamships under contract with the Navy Department were carrying U.S. Mail from New York to California via the Isthmus of Panama.[2] This was before the construction of the canal. When the ships reached Panama, the mail was taken off and transported in canoes or on pack animals – and later by railroad – about 50 miles to the Pacific coast. Another steamship collected the mail on the Pacific side and headed north. The aim was to get a letter from the East Coast to California in three to four weeks. Although that goal was often missed, steamships remained a vital link between East and West until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

In the late 19th century, while the use of steamboats decreased in many places, it increased in Washington, Oregon and Alaska. Nationwide, steamboat mail route mileage peaked in 1906 at 42,181 miles – about a third of them serving communities in Alaska.

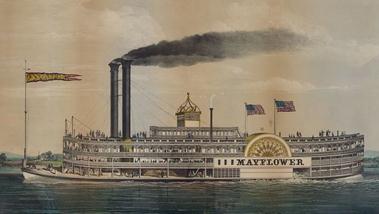

The Mayflower, 1855

In December 1855 – less than a year after entering service between St. Louis and New Orleans – the Mayflower was destroyed by fire. The average lifespan of an antebellum steamboat on the Mississippi River was five to six years. Daily hazards included explosions, fires, collisions and the submerged, hull-piercing deadwood called “snags.”

(Currier & Ives print, 1855,

courtesy Library of Congress)

HISTORIAN

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE

JANUARY 2013

[1] Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1835, in Public Documents Printed by Order of the Senate of the United States, First Session of the Twenty-Fourth Congress, Begun and Held at the City of Washington, December 7, 1835, and in the Sixtieth Year of the Independence of the United States, Volume 1, Number 1 (Washington, DC: Gales & Seaton, 1836), 394.

[2] In 1847 Congress authorized the Secretary of the Navy to enter into contracts with private companies for the construction and operation of mail-carrying steamships. The plan was for the steamships to be convertible to warships if the need arose. Congress’ intent was to simultaneously upgrade the U.S. naval fleet, provide mail service to California, and subsidize American steamship companies so they could better compete with England’s successful Cunard line.